By Dorothy Kaplan, Ph.D.

July 14, 2023

As a behavioral health provider, service member or veteran with lived experience, or a concerned family member, you may have experienced crisis care that exacerbated rather than eased emotional distress. An individual in acute suicidal crisis may receive only custodial care in an emergency department while waiting hours to days for an inpatient mental health bed. A more informed approach to mental health crisis response and suicide prevention consists of a mental health crisis line staffed by trained responders and accessible by anyone, anywhere, anytime for immediate support in real time. In an ideal system, the crisis line serves as the coordinating hub for connection to timely mental health resources, mobile mental health crisis teams, and crisis receiving and stabilization centers.1

It’s a launch!

The Veterans Crisis Line was established in 2007 in a legislative act that amended public law and directedthe Secretary of Veterans Affairs to develop and implement a comprehensive suicide prevention program (Public Law 110-110).2 The National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020 designated 988 as the universal telephone number for the national suicide prevention and mental health crisis hotline system (Public Law 116-172).3 On July 16, 2022, the easy-to-remember three-digit 988 replaced the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and Veterans Crisis Line phone numbers.4,5

Comparing 988 data (excludes the VCL) for May 2023 to May 2022, calls increased by 45%, chats increased by 52%, and texts increased by 938%. The average speed to answer contacts (calls, chats, texts) in May 2023 was just 35 seconds. The average contact time with a user ranged from just under 13 and a half minutes for a call to 49 minutes for a text conversation.6

While 988 is a new phone number, veterans and service members who press 1 are still routed to trained responders specialized in supporting veterans, service members and their families.7 The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline recently began offering the option of connecting with counselors specialized in supporting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other gender minority youth and young adults (text Q to 988 or dial 988, then press 3).8 In addition to the specialized resources of 988, the Veterans Crisis Line offers multiple ways for service members and veterans to engage with responders including text (text 838255), chat (https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/get-help-now/chat), and telephone calls (dial 988, then press 1).

Since its inception, the VCL has received more than 6.8 million calls, 821,000 chats, and 299,000 texts. These contacts have led to more than 1.3 million referrals to suicide prevention coordinators for follow up and care coordination with VA, DOD, and community resources.9 In May 2023, 988 routed 469,023 contacts, including 66,529 calls, to the Veterans Crisis Line.10

Suicide prevention lifelines are effective

Most 988 callers resolve their immediate concerns over the phone and fewer than 2% of calls require connection to emergency services such as law enforcement or Emergency Medical Services.11. In a study of high-risk callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, most recipients reported that this intervention stopped them from taking their life (79.6%) and kept them safe (90.6%).12 In addition to de-escalation and linkage to services, these crisis lifelines now also provide brief interventions such as the safety planning intervention, which is feasible and valuable during crisis calls and mitigates future risk.13

The SPI is a semi-structured interview in which a crisis call counselor and an individual in distress collaborate to develop a list of warning signs, coping strategies, and resources to utilize during the crisis.14

Text, chat, and third-party callers

Younger persons are more likely to choose text or chat rather than a telephone call for mental health and suicide crises, with more than three-quarters under the age of 25.15, 16 Approximately three quarters of crisis text line users are female and approximately half identify as a member of a racial minority; likewise, 47.8% identify as sexual and gender minorities including 2.7% trans-male or trans-female.17 Crisis text lines serve a highly distressed population with high symptom levels of depression and anxiety; nearly 25% reporting suicidal ideation and 10% a plan.18 A recent study found that among the chatters who endorsed either current or recent suicide ideation, nearly half reported being less suicidal at the end of the chat; a comparable reduction to that found after more time-intensive interventions.19

Approximately 25% of calls to crisis lines are from concerned friends and family. Third-party callers are significantly more likely than persons at risk to be female and middle aged or older. For over 40% of calls, counselors were able to identify steps that they or the caller could take to mitigate suicide risk and avoid emergency service involvement. Emergency services contact is more likely when the person at risk is either amid a suicide attempt or within a few hours of a planned suicide.20

Encouraging the use of crisis lines to prevent suicide

Eighty-seven percent of VCL users report satisfaction with the VCL.21 Nevertheless, some service members, veterans, and their families may be reluctant to reach out to 988 and the VCL. Songs and storytelling about individuals who manage suicidal crises by reaching out to suicide prevention lifelines may provide a medium to promote help seeking and prevent suicides. In 2017, the song “1-800-273-8255" — a nod to the National Suicide Prevention Line phone number — was released, and explores suicidal crisis, hope, help-seeking, and recovery. During the 34 days when public attention to the song was greatest, daily calls to the Lifeline number increased 6.9% and suicides decreased by 5.5%, equating to an estimated 245 fewer suicides.22

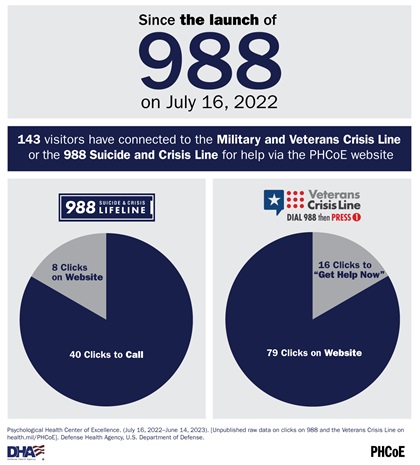

PHCoE website users clicks for help to crisis lines

Since the launch of 988, 143 PHCoE website visitors have been connected to the Veterans and Military Crisis Line (95 clicks) or 988 (48 clicks) websites. The main PHCoE webpage was the source for 87 of these clicks, with articles or blogs about suicide generating most of the other clicks to these crisis line websites.23 Of those who accessed the Veterans Crisis Line, 79 clicked “Get Help Now” with 16 clicks to “Chat Online” and 63 clicks for other help offered on the Military Crisis Line website.

The successful launch of 988 provides an opportunity to build on this initial success. It allows us to consider how we can most effectively approach mental health and substance use disorders, and how we might expand and evolve our crisis response system while transforming mental health and suicide prevention.24

If you have an emergency or are in crisis, please contact the Military Crisis Line or the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988.

To get help from the Military and Veterans Crisis Line outside the continental U.S. call:

- Europe: 844-702-5495 or DSN 988

- Pacific: 844-702-5493 or DSN 988

- Southwest Asia: 855-422-7719 or DSN 988

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). National guidelines for behavioral health crisis care – A best practice toolkit.

- Joshua Omvig Veterans Suicide Prevention Act, Pub. L. No. 110–110, Stat. 2661 (2007). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-110publ110/html/PLAW-110publ110.htm

- National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116–172, Stat. 2661 (2020). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-116publ172

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022). U.S. transition to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline begins Saturday. https://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/20220715/us-transition-988-suicide-crisis-lifeline-begins-saturday

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2022). National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2022/2022-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). 988 lifeline performance metrics. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/988/performance-metrics

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). Veterans Crisis Line. https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/about/what-is-988

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). 988 frequently asked questions. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/988/faqs#about-988-basics

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2022). National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2022/2022-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). 988 lifeline performance metrics. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/988/performance-metrics

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). 988 frequently asked questions. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/988/faqs#about-988-basics

- Gould, M. S., Lake, A. M., Galfalvy, H., Kleinman, M., Munfakh, J. L., Wright, J., & McKeon, R. (2018). Follow-up with callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Evaluation of callers' perceptions of care. Suicide & Life-threatening Behavior, 48(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12339

- Labouliere, C. D., Stanley, B., Lake, A. M., & Gould, M. S. (2020). Safety Planning on Crisis Lines: Feasibility, Acceptability, and perceived helpfulness of a brief intervention to mitigate future suicide risk. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 50(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12554

- Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. (2019). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/mh/srb

- Gould, M. S., Chowdhury, S., Lake, A. M., Galfalvy, H., Kleinman, M., Kuchuk, M., & McKeon, R. (2021). National Suicide Prevention Lifeline crisis chat interventions: Evaluation of chatters' perceptions of effectiveness. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 51(6), 1126–1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12795

- Gould, M. S., Pisani, A., Gallo, C., Ertefaie, A., Harrington, D., Kelberman, C., Green, S. (2022). Crisis text-line interventions: Evaluation of texters' perceptions of effectiveness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 52, 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12873

- Gould, M. S., Pisani, A., Gallo, C., Ertefaie, A., Harrington, D., Kelberman, C., Green, S. (2022). Crisis text-line interventions: Evaluation of texters' perceptions of effectiveness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 52, 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12873

- Pisani, A. R., Gould, M. S., Gallo, C., Ertefaie, A., Kelberman, C., Harrington, D., Weller, D., & Green, S. (2022). Individuals who text crisis text line: Key characteristics and opportunities for suicide prevention. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 52(3), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12872

- Gould, M. S., Pisani, A., Gallo, C., Ertefaie, A., Harrington, D., Kelberman, C., Green, S. (2022). Crisis text-line interventions: Evaluation of texters' perceptions of effectiveness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 52, 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12873

- Gould, M. S., Lake, A. M., Kleinman, M., Galfalvy, H., & McKeon, R. (2022). Third-party callers to the national suicide prevention lifeline: Seeking assistance on behalf of people at imminent risk of suicide. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 52(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12769

- Johnson, L. L., Muehler, T., & Stacy, M. A. (2021). Veterans' satisfaction and perspectives on helpfulness of the Veterans Crisis Line. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 51(2), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12702

- Niederkrotenthaler, T., Tran, U. S., Gould, M., Sinyor, M., Sumner, S., Strauss, M. J., Voracek, M., Till, B., Murphy, S., Gonzalez, F., Spittal, M. J., & Draper, J. (2021). Association of Logic's hip hop song "1-800-273-8255" with Lifeline calls and suicides in the United States: Interrupted time series analysis. British Medical Journal, 375, e067726. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-067726

- Psychological Health Center of Excellence. (July 16, 2022-June 14, 2023). [Unpublished raw data on clicks on 988 and the Veterans Crisis Line on health.mil/PHCoE]. Defense Health Agency, U.S. Department of Defense.

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, American Psychiatric, Association American Psychological Association, Massachusetts Association for Mental Health, Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute, Mental Health America, National Association for Behavioral Healthcare, National Alliance on Mental Illness, National Council for Mental Wellbeing, One Mind, Peg’s Foundation, Steinberg Institute, The Kennedy Forum, Treatment Advocacy Center, & Well Being Trust. (2020). Consensus approach and recommendations for the creation of a comprehensive crisis response system. https://wellbeingtrust.org

Dorothy A. Kaplan, Ph.D. is a contracted subject matter expert at the Psychological Health Center of Excellence in the Research Adoption Section supporting the development of evidence-based clinical support tools and resources for providers, patients, and their families.